Symbolism of Brigid’s Cross

This contains ritual gathering of materials, construction of the various crosses, uses of them and disposal of them. I have compiled this from numerous sources. The majority of my post is from this rearranged article (unless otherwise stated)

by Annie Loughlin

http://www.tairis.co.uk/celebrations/making-the-cros-bride/

Traditionally it’s straw or rushes that are used to make the crosses (or sometimes wood), but folklorist Thomas Mason has also noted the use of leather, grasses, wire, and cloth.(4) Today anything that’s workable will do: Pipe cleaners, wool, lollipop sticks, paper, ribbons, raffia… All kinds of things. There is also a tradition of drawing the crosses onto the side of buildings or onto the fore-arm or forehead of each person within the household, using a charred stick,(5) and smaller crosses (often of less traditional styles) made be worn by

children.(6)

In making the crosses, where rushes are used it’s said that they should be pulled and not cut.(14) It’s clear here that the reason is that to cut them means exposing them to iron, which the spirits have an aversion to. (You can cut the ends to size using your fingernails or a sharp plastic or wooden knife to avoid using iron – to do so, it’s said, means the Good Folk and Brìde will stay away and they won’t give their blessing.) They are usually collected during the day on January 31st, and are then left outside until the evening when they’re brought in with great ceremony, although who does this may vary. In some parts of Ireland it’s a member of the family who goes to gather the straw or rushes (usually in secret – no one must know what they’re doing), and it may be left to the man of the house to bring the materials in.(15) In other parts (such as Galway and Aran) it’s traditional for the Biddy Boys to collect the rushes and then they bring them round to the houses and ask to be let in, in the name of Brìde:

Going up to the door, the boys shout seven times, “Leig asteach Brighid” (Lig aschiŏkh’ Breej), “Let Bridget enter,” while to each demand those within reply, “Leig a’s céad fáilte romhad” (Lig os caedh fawlcha roath), “Enter and a hundred welcomes before you.”(16)

In still other parts of Ireland (such as Donegal), it’s girls who have the job of bringing the rushes in, and they take on the role of Brìde themselves. In this case it’s usually the eldest daughter who does this, unless there is a younger child who shares her name with the goddess (or saint, depending on your point of view).(17)

The weaving must be done sunwise, from left to right.

All in all there are at least 23 different forms of cros Bríde recorded by T. G. F. Paterson, 7 accounting for the different shapes, styles, and materials that might be used in making them, though there are surely many more than that (I’ve seen some examples with only two arms – essentially a v-shape – that aren’t listed by Paterson). Sean Ó Duinn, however, groups them all into seven main categories:

The four-armed or ‘swastika’ type

The three-armed type

The diamond or ‘lozenge’ type

The interwoven type

St Brigid’s Bow

St Brigid’s bare cross

The Sheaf cross (8)

I have listed the types in order of symbolism

~

Number 1

The Diamond or ‘Lozenge’ type

God’s Eye

It has been recorded that where all the different types were known, they were used in different ways. The lozenge cross was hung in the house… Each of them was sprinkled with water taken from the nearest well dedicated to St. Brigid, a gesture which ensured the safety of the occupants of the building in question be they animal or human.

Olive SHARKEY in the 1996 #2 issue of “Irish Roots” magazine published in Cork

For her profile and book: http://www.obrien.ie/olive-sharkey https://www.obrien.ie/ways-of-old

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/IrelandGenWeb/2011-02/1296764871

How to Make

Instructions for even very small children (with an adult to supervise):

http://www.auntannie.com/FridayFun/GodsEye/

Symbolism

Irish Gaelic suil, which means “eye,” i.e. the Sun, the eye of the heavens.

Eric Partridge, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, entry “Sun”

Brighid is a Sun deity.

~~

Number 2

V Shape, Chevron, Welsh Border Fan

“(I’ve seen some examples with only two arms – essentially a v-shape – that aren’t listed by Paterson).”

T. G. F. Paterson, ‘Brigid’s Crosses in County Armagh,’ in Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society

Volume 11, No. 1, 1945.

Annie Loughlin

http://www.tairis.co.uk/celebrations/making-the-cros-bride/

How to Make

This maybe it: a Welsh Border Fan: http://colorful-crafts.com/straw-weaving-welsh-border-fan/

Symbolism

“A Chevron is an ancient symbol, appearing as a V-shape.

Generally the chevron symbol represents dutiful service given freely.

This Celtic symbol can also represent the peaks and valleys in our lives and it also serves as a symbol of protection as it’s peak and “sloped arms” are reminiscent of a roof.”

https://www.buildingbeautifulsouls.com/symbols-meanings/celtic-symbols-and-meanings/

Or it could be the Gnostic Law of Opposites. This is the doctrine of bringing order out of chaos, of reconciling the two opposites, evil and good, light and dark.

Dutiful Service Given Freely

“The Vita Brigitae: Life of Brigid, written by Cogitosis – who may have been a Brigidine monk in Kildare in the latter half of the 7th century – is the earliest written record. In the Life, the main emphasis is on Bridgit’s faith, her healing powers, her skill with animals, her hospitality, her generosity, and, especially, her concern for the poor, the oppressed, or the embarrassed.”

[just to clarify this is Saint] Bridget and Kildare article

by Sister Rita Minehan

in Brigit: Sun of Womanhood

Edited by Patricia Monaghan and Michael McDermott

Published by Goddess Ink Ltd, Las Vegas, 2013

I view the V shape as duality coming from the single source Dea, She who is Spirit.

~~~

Number 3

Three Arm Cross or Triskele

“The most primitive form is the three arm cross or triskele, which is associated with cattle, and is placed in the byre or cowshed for protection. (The wealth of a person in Celtic society was based on cattle not land.) The triskele was not blessed by the Church.”

http://www.crosscrucifix.com/brigid2.htm

In Scotland she was invoked as “Milkmaid Bride,” or “Golden-haired Bride of the kine,” patroness of cattle and dairy work. Medieval Christian art often depicts her as holding a cow, or carrying a pair of milk-pails.

http://www.chalicecentre.net/february-celtic-year.html

“Apparently cow’s milk was the original communion but was eventually banned by the Trullan council in 692. Milk, along with honey, was given to the newly-baptised as a symbol of regeneration.”

https://www.whitedragon.org.uk/articles/brighid.htm

“She is sometimes mentioned as a triple goddess i.e. three sister goddesses named Brid; one goddess associated with poetry and traditional learning in general; one associated with the smith’s art; and the third associated with healing.”

http://kildarelocalhistory.ie/kildare/history-of-kildare-town/saint-brigid/

Different areas tend to favour different styles of cross, with the three-armed version, for example, being centred around the north of Ireland in parts of Donegal, Armagh, and Antrim.(12)

Olive SHARKEY on St. Brigid’s Crosses / Ritual of ‘Turning the Sod’ [sod is a clump of soil]

“The three-legged cross was widely known in the NW of Ireland, and in most parts of Ulster, and always reminded Olive of the Isle of Man symbol.”

Olive SHARKEY in the 1996 #2 issue of “Irish Roots” magazine published in Cork

For her profile and book: http://www.obrien.ie/olive-sharkey https://www.obrien.ie/ways-of-old

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/IrelandGenWeb/2011-02/1296764871

How to Make

To make a three-armed triskele type cross, the principle is pretty much the same as with the four-armed cross, except you start off with two rushes, both of which are folded in half (only one is folded in the four-armed version).

See photo sequence on: http://www.tairis.co.uk/celebrations/making-the-cros-bride/

Symbolism

I view this symbol as representing the Deanic Holy Trinity / Triunity.

~~~~

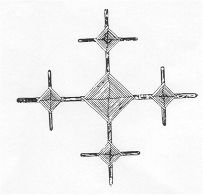

Number 4

The four-armed or ‘swastika’ type

For the St. Brighid Cross, instead of a circular sun, we can imagine sun rays.”

http://www.seiyaku.com/customs/crosses/brighid.html

“Of them all, it’s the four-armed ‘swastika’ version that’s perhaps the most common and recognisable type of cross of them all because of its use in corporate logos by a number of different companies in Ireland (including the Department of Health).13”

Olive SHARKEY on St. Brigid’s Crosses / Ritual of ‘Turning the Sod’ [sod is a clump of soil]

“Some historians tend to refer to the standard cross as a swastika, but it lacks the essential element of the swastika, that of the sharp bends on the arms.

It has been recorded that where all the different types were known, they were used in different ways. …the standard form in the cow-byre… Each of them was sprinkled with water taken from the nearest well dedicated to St. Brigid, a gesture which ensured the safety of the occupants of the building in question be they animal or human.”

Olive SHARKEY in the 1996 #2 issue of “Irish Roots” magazine published in Cork

For her profile and book: http://www.obrien.ie/olive-sharkey https://www.obrien.ie/ways-of-old

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/IrelandGenWeb/2011-02/1296764871

How to make

Simple illustrations: https://fisheaters.com/stbrigidscross.html

Symbolism

I have 2 ideas.

It symbolises Supernal Sun, Celestial Mother God / Madria Dea

I view the St. Brighid’s Cross much as David Kay views the swastika, symbolising the turning of the world from the impression of the spirit / Supernal Sun.

The square centre meaning “In fact, when I see squares in my readings/interpretations, I always think of foundations (like homes, buildings or even plots of earth squared off for gardening). Squares are symbolic cues for me, and they speak to me about hearths, homes, matter and materialistic concepts. …In the Chinese way of thought, the square is a symbol for earth with the circle representing the shape of the heavens. This lends further weight to the earthy, grounded nature of the square symbol meaning. …Indeed, our ancestors transitioned from nomadic life by exchanging tents and teepees (circular) for solid square-based structures.”

www.whats-your-sign.com/square-symbol-meaning.html

~~~~~

Number 5

St Brigid’s Bare Cross

The “bare cross” defined by Ó Duinn may also be simply referred to as the Latin or Greek type – a cros Bríde that most closely resembles the Christian cross.

Symbolism

David Kay in https://mydevotionstodea.wordpress.com/2016/12/31/madrian-thoughts-on-manifestation-and-the-cross-symbol/

“A vertical line is the reflection of the spirit onto the material plane, creating a cross. Where the vertical line touches the horizontal line is the quintessence, the reflection of the spirit into matter, and contains all the possibilities of manifestation.

The horizontal reflection of the vertical line creates the cross of matter, the four arms being the four elements. At the centre, where the four arms meet, they are in equilibrium, reflecting the spirit. The four arms are the reflection of the spirit into the separativeness of manifestation, moving further away from each other as the move further away from the centre.”

I would add that the four arms are the directions and elements:

The Madrian system is different: East is Water, South is Fire, West is Earth and North is Air, with the central point being She who is Spirit, Dea.

~~~~~~

Number 6

Bogha Bhride (Brigid’s Bow)

Olive SHARKEY on St. Brigid’s Crosses / Ritual of ‘Turning the Sod’ [sod is a clump of soil]

“A much more complicated cross was known in a few parts of Connaught, also in Munster and parts of Ulster, fashioned by interlacing strands of straw, rushes or reed in a criss-cross type pattern.

It has been recorded that where all the different types were known, they were used in different ways. The interlaced variety in the stable. [Donkeys were common]. Each of them was sprinkled with water taken from the nearest well dedicated to St. Brigid, a gesture which ensured the safety of the occupants of the building in question be they animal or human.”

Olive SHARKEY in the 1996 #2 issue of “Irish Roots” magazine published in Cork

For her profile and book: http://www.obrien.ie/olive-sharkey https://www.obrien.ie/ways-of-old

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/IrelandGenWeb/2011-02/1296764871

I am guessing that this is “a cross made with a “binding knot,” which acts as a barrier to evil spirits.”

As I cannot find an illustration alongside the description of a Bogha Bhride / Brigid’s Bow.

“This shows affinities with the Swabian and Tyrolean magical protector known as a Schratterlgatterl, which is an interweaving of a number of sticks employed as a barrier beyond which evil spirits cannot pass.”

http://www.celticcultureblog.tk/cross/craft-techniques-and-celtic-ornament.html

Symbolism

In it’s simplest form (often created in schools), it starts as one bundle divided into two. Then each of these two are interwoven in three strands.

I see this as (1) Dea Matrona, the Great Mother emanating into (2) Dea Madria, the Celestial Mother and then emanating into (3) Dea Matria, God who is immanent (in creation).

As it’s final form it is 2 bundles of three strands interwoven. The number 6, which in a cross symbolises matter and relates to the wheel of Moira (karma) in Madrian thealogy.

To me the 2 meaning duality with 3 meaning Divinity.

She who is Spirit, Dea threaded through matter and our incarnate life.

The more complex forms again relate to Sacred Numbers.

Some of which I have information about. I am writing a future article about The Celestial Janyati and Sacred Numbers.

~~~~~~~

Number 7

The Sheaf Cross

“In partnership with the goddess Brìghde, the Cailleach is seen as a seasonal deity or spirit, ruling the winter months between Samhainn (1 November or first day of winter) and Bealltainn (1 May or first day of summer), while Brìghde rules the summer months between Bealltainn and Samhainn. Some interpretations have the Cailleach and Brìghde as two faces of the same goddess, while others describe the Cailleach as turning to stone on Bealltainn and reverting to humanoid form on Samhainn in time to rule over the winter months. Depending on local climate, the transfer of power between the winter goddess and the summer goddess is celebrated any time between Là Fhèill Brìghde (1 February) at the earliest, Latha na Cailliche (25 March), or Bealltainn (1 May) at the latest, and the local festivals marking the arrival of the first signs of spring may be named after either the Cailleach or Brìghde.

McNeill, F. Marian (1959). The Silver Bough, Vol.2: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Candlemas to Harvest Home. William MacLellan. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-85335-162-7.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cailleach

Of these, Paterson has noted that some of the plaited versions (the Sheaf Cross, as Ó Duinn calls them) have harvest knots fashioned into them, which are made from the last sheaf cut from the field at harvest-time (called the Cailleach or ‘Cailliagh’).(9) The “interwoven type” generally consists of several crosses worked together onto a larger frame, as illustrated here from Henry Crawford:

From Henry Crawford’s ‘Crosses of Straw and Twigs from County Roscommon,’ in JRSAI Vol 38 No. 4, (1908)

Some examples of these interwoven crosses have even more crosses on them – Mason reports as many as fourteen in one example he saw during his research in the field – and the thought here is that “the more frequent the repetition, the greater and surer will be the blessing which ensues.”(10)

Symbolism

The County Waterford and County Roscommon illustrations are quincunx. This is a geometric pattern consisting of five points arranged in a cross, with four of them forming a square or rectangle and a fifth at its center.[1] It forms the arrangement of five units in the pattern corresponding to the five-spot on six-sided dice, playing cards, and dominoes.

[1] Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed., as quoted by Pajares-Ayuela (2001).

See also the 5 provinces of Ireland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quincunx

In Madrian thealogy these are the 4 elements and directions with the 5th being the quintessence Spirit in the centre.

Blessing the house

…in Co. Leitrim a description of the rites involved tells us:

When the cross was made the head of the house went round the house with it and placed it in every window and door round the house and said at each entrance or window, “St Brigid save us from all fever, famine and fire.” He then came in and placed the cross over the kitchen door.(19)

Although not specified, this was presumably carried out deiseil (sunwise) about the house, and the description shows that it is clearly a saining rite. Here, instead of water or a rowan charm, it is simply the cros Bríde itself that provides the focus and agent for blessing and protection upon the household.

The old cross from the previous year is traditionally moved to make way for the new cross. In most cases the old cross is simply moved up to the rafters or to an outbuilding where they then accumulate.(23) When a newlywed couple starts their married life in a new home it’s traditional for them to clear out the old crosses and start afresh. In many traditional houses, the number of crosses up in the rafters would show how many years the couple had been married, but in some parts of Ireland crosses that have begun to rot or are no longer able to stay in one piece may be taken down and buried out in the field to impart Brìde’s blessing on the crops that grow there (or the livestock who feed there). Alternatively, they are crumbled into dust between the fingers and spread over the land, or else they may be burned.(24) According to Paterson, the reason for their being burnt isn’t clear, but it may be connected with the tradition of Brigid’s perpetual flame.(25) Regardless of why this is done, the ashes may be kept for healing purposes for both livestock and people.(26)

Gifting

…the crosses may also be made as gifts; to give a cros Bríde to a friend or loved one is to give them a blessing of Brìde herself and it’s considered to be a great sign of affection.(30) The friends of newlyweds would place a cross in the thatch of their new home as they moved in, to bless the couple in their new life together.(31)

References for http://www.tairis.co.uk/celebrations/making-the-cros-bride/

(1) Translating to “Brigid’s Cross” and “Brigid’s Bow,” respectively. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2004, p959.

(2) Evans, Irish Folk Ways, 1957, p268; Ó Duinn, The Rites of Brigid, 2005, p157; Danaher, The Year in Ireland, 1972, p18.

(3) Henry Crawford, ‘Crosses of Straw and Twigs from County Roscommon,’ in JRSAI Vol 38 No. 4, 1908, p395.

(4) If there’s a traditional wood (or woods) that’s used – one might presume it would be a protective wood such as rowan or birch, for example – it’s not usually specified by the folklorists writing about the crosses. Henry Crawford, however, noted that “they are sometimes made of peeled willow twigs…” I presume willow would be an appropriate wood of choice because it’s very flexible and easy to work with, but Crawford’s reference to it doesn’t mean that it’s the only wood that’s used and there’s no mention of whether its use indicates a deeper significance. O’ Sullivan gives examples of several multi-form crosses that use bog-wood – wood recovered from bogs, so of no specific type, in his article. In general, the preference for straw or rushes seems to be more to do with availabilty (straw being used in predominantly agricultural areas, rushes in predominantly pastoral) so presumably wood it the same. See Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p160; Crawford, ‘Crosses of Straw and Twigs from County Roscommon,’ in JRSAI Vol 38 No. 4, 1908, p395; O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, Plate 2a.

(5) Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p162.

(6) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, p80.

(7) Paterson, ‘Brigid’s Crosses in County Armagh,’ in Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society Volume 11, No. 1, 1945, Plates I and II.

(8) Ó Duinn, The Rites of Brigid, 2005, p121.

(9) ‘Such a cross presents to the mind a relationship with the harvest and makes one wonder whether Brigid took over some of the attributes of the Calliagh, besides those of her pagan namesake.’ Paterson, ‘Brigid’s Crosses in County Armagh,’ in Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society Volume 11, No. 1, p19; Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p166. The fact that there is an association between the Cailleach and Brìde here is very intriguing, especially considering their relationship in Scotland.

(10) Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p164.

(11) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, p71; 80.

(12) Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p162.

(13) O’Riordan, ‘The Cult of St Brigid,’ in The Furrow Volume 2 No. 2, 1951, p91.

(14) Evans, Irish Folk Ways, 1957, p268; Ó Duinn, The Rites of Brigid, 2005, p157.

(15) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp65-66.

(16) See Mooney, The Holiday Customs of Ireland, 1889, pp379-384.

(17) Mooney, The Holiday Customs of Ireland, 1889, pp379-384; O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp65-66.

(18) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp65.

(19) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp67.

(20) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp67.

(21) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp67.

(22) Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, pp164-165.

(23) Paterson, ‘Brigid’s Crosses in County Armagh,’ in Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society Volume 11, No. 1, 1945, p16.

(24) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, pp68-70.

(25) 25 Paterson, ‘Brigid’s Crosses in County Armagh,’ in Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society Volume 11, No. 1, 1945, p16.

(26) O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, p71.

(27) Writing in 1689: ‘I went abroad into the Country, where I found all the Houses deserted for several miles; most of them that I observed, had Crosses on the Inside above the Doors, upon the Thatch, some made of Wood; and others of straw or rushes, finely wrought; some Houses had more, and some less: I understood afterwards, that is the custom among the Native Irish, to set up a new Cross every Corpus Christi day; and so many years as they have lived in such a house, as many Crosses you may find; I asked a Reason for it, but the Custom was all they pretended to.’ O’ Sullivan, St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in Folk Life Volume 11 Issue 1, 1973, p62.

(28) As noted in the article on Là Fhèill Brìghde, Evans suggests the three-armed crosses are evidence of older type crosses stemming from pagan times, being reminiscent of the triskele, with the four-armed crosses being adopted during Christian times. There’s no hard evidence for this but the fact that the triskele just isn’t a cross (if the cross is supposed to represent a Christian cross) doesn’t make it seem like the most Christian of choices.

Mason, in trying to procure a triskele-type cross from a farmer, was met with a lot of resistance and excuses leading him to conclude that the triskele form had ‘greater significance’ than the four-armed type. He noted that the four-armed swastika type was usually found in the home while the triskele-type was found in the byre, but Ó Súilleabháin contradicts this, saying this seems to be the exception rather than the rule, and specific styles of cross do not appeared to be favoured for certain uses. Mason, however, feels that the reluctance to part with a triskele-type cross is evidence of their pre-Christian and therefore more potent and authentic significance. Evans, Irish Folk Ways, 1957, p268; Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, pp162-163.

(29) Mason, ‘St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p166.

(30) O’ Riordan, ‘The Cult of St Brigid,’ in The Furrow Volume 2 No. 2, 1951, p91.

(31) Concannon, ‘The Holy Women of the Gael,’ in The Irish Monthly Vol 45, 1917, p86.

(32) Mason,’St Brigid’s Crosses,’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Volume 75 No. 3, 1945, p162.

(33) See here.

(34) This is how I make them but O’ Sullivan describes starting off with one rush folded in half with the other bent into the angles of where the second and third arms will be. Having said that, he gives two methods for making the swastika-type, one of which involves starting off as I do here (and then following on to make four arms instead of three). As with just about everything else, traditions and methods vary and there’s no real wrong answer here. p76-77.

Exceptional post with great examples and history, as well as Deanic correspondences.

LikeLike

Thank you ArchMadria Kathi

LikeLike